Here is the uncomfortable truth about teaching: everything you do in the classroom—your grading practices, your retake policy, your lesson plans, your assignments, the way your desks are arranged, the way you talk about your students, your writing instruction, the homework you assign, the amount of homework you give—is political. This is true whether you think about politics all the time or you’ve never thought about politics a day in your life.

If you’re reading this and thinking, “Yikes—that may be true of Mr. Ejzak, but my teaching practices have always been totally neutral,” you’ve just fallen into the oldest trap: assuming that the status quo—the “standard way of doing things”—is apolitical. It’s not.

Of course, I’m not talking about politics in its most simplistic sense (“How do you feel about Joe Biden?”). I’m talking about the fundamental ideologies that undergird politics. More importantly, I’m talking about the structures and systems we participate in on a daily basis—structures that either a) empower us to make our own choices or b) make our choices for us (“do this or else”). As teachers, even though we’re beholden to a larger capitalist system, we’re also partially responsible for creating these structures and systems in our own classrooms—and as Spiderman’s uncle once said, “With great power comes great responsibility.” In other words, a classroom is a miniature society: you can either create a mini dystopia, a mini utopia, or—most common—just replicate the compliance-based authoritarian structures that already exist in the outside world.

This last option is the most dangerous because it’s the easiest to fall back on (and the easiest to justify). Teaching is political in an extremely challenging way because the teaching profession is inherently authoritarian, rooted in class hierarchies and capitalism and white supremacy. This means that any time a teacher relaxes into “traditional, time-honored” teaching practices—as I often do; I’m not immune to any of this—they run the risk of subtly reinforcing an authoritarian status quo in which the teacher holds all the power (as evaluator, as taskmaster, as gatekeeper, as chooser of assignments and texts) and the student gradually accepts that they have none (no power to choose assignments, no power to choose texts, no power to pursue or write about their own interests, no power to set their own goals, no power to evaluate themselves or gauge their own progress).

This last option is the most dangerous because it’s the easiest to fall back on (and the easiest to justify). Teaching is political in an extremely challenging way because the teaching profession is inherently authoritarian, rooted in class hierarchies and capitalism and white supremacy. This means that any time a teacher relaxes into “traditional, time-honored” teaching practices—as I often do; I’m not immune to any of this—they run the risk of subtly reinforcing an authoritarian status quo in which the teacher holds all the power (as evaluator, as taskmaster, as gatekeeper, as chooser of assignments and texts) and the student gradually accepts that they have none (no power to choose assignments, no power to choose texts, no power to pursue or write about their own interests, no power to set their own goals, no power to evaluate themselves or gauge their own progress).

If students are disengaged, then, it is for the same reason a gas station attendant might be disengaged: powerlessness encourages despondency. Human beings wilt under authoritarian institutions. (My AP Lang students will recognize this as a watered down version of our friend Paulo Freire.)

|

Let’s consider this in the context of ChatGPT. In the Brooks English Department (and in high schools and universities all over the country), there are a lot of people freaking out about chatGPT right now. And rightfully so: What’s the point of English class when anyone can auto-generate an essay (or an email, or a research paper, or a short story) on command? Aside from general morality and fear of getting caught, what’s to stop the next generation from having AI write literally everything for them?

|

Well, here’s one answer: Genuinely caring about the assignment. Seeing value in it. Having a personal investment in it. Believing that it’s possible to do it (and to do it well) in the time allotted. This may sound like naivete. It’s not. It’s at the heart of an anti-authoritarian teaching practice.

The truth is that students are not equally likely to use ChatGPT on every writing assignment. Yes, we’ll probably receive a small handful of ChatGPT essays in every batch—at this point, these are still mercifully easy to identify—but the conditions of the writing assignment often determine how likely a student is to cheat. Cheating is not an inevitable fact of life. Students are not natural-born cheaters. In other words, cheating is not the consequence of “bad kids”; it is the consequence of larger systems and structures that encourage cheating. Too often, teachers, in their (understandable) exasperation over cheating, forget to ask fundamental, structural questions.

So when I get a ChatGPT paper, I have two options:

a) Get mad. Rail against “kids these days.” “How dare they,” etc. “Back when I was your age, I would never,” etc.

OR

b) Ask myself the following questions:

1) Did I give them a reasonable amount of time—in class and out of class—to complete this piece of writing?

2) Did I give them enough scaffolding, support, and model texts to understand my expectations?

3) Did I give them enough individualized feedback to understand my expectations?

4) Did I spend time on the writing process—annotation, outline, rough draft, revisions, final draft—rather than just having them submit a final draft?

5) Did I let them choose WHAT they’re writing about (the subject/text)?

6) Did I let them choose HOW they write this paper? (Or is it extremely formulaic?)

7) Did I successfully remove the external motivator of “grades” from this writing process so that students are invested in the process for its own sake? (Or is there a big scary grade waiting for them at the end that will partially determine their GPA/financial security/future opportunities?)

The truth is that students are not equally likely to use ChatGPT on every writing assignment. Yes, we’ll probably receive a small handful of ChatGPT essays in every batch—at this point, these are still mercifully easy to identify—but the conditions of the writing assignment often determine how likely a student is to cheat. Cheating is not an inevitable fact of life. Students are not natural-born cheaters. In other words, cheating is not the consequence of “bad kids”; it is the consequence of larger systems and structures that encourage cheating. Too often, teachers, in their (understandable) exasperation over cheating, forget to ask fundamental, structural questions.

So when I get a ChatGPT paper, I have two options:

a) Get mad. Rail against “kids these days.” “How dare they,” etc. “Back when I was your age, I would never,” etc.

OR

b) Ask myself the following questions:

1) Did I give them a reasonable amount of time—in class and out of class—to complete this piece of writing?

2) Did I give them enough scaffolding, support, and model texts to understand my expectations?

3) Did I give them enough individualized feedback to understand my expectations?

4) Did I spend time on the writing process—annotation, outline, rough draft, revisions, final draft—rather than just having them submit a final draft?

5) Did I let them choose WHAT they’re writing about (the subject/text)?

6) Did I let them choose HOW they write this paper? (Or is it extremely formulaic?)

7) Did I successfully remove the external motivator of “grades” from this writing process so that students are invested in the process for its own sake? (Or is there a big scary grade waiting for them at the end that will partially determine their GPA/financial security/future opportunities?)

|

For me, the answers to the first four questions are usually “yes,” and the answers to the last three questions are usually “no.” This is a good start, but it’s not enough. My teaching practices, like most educators’ teaching practices, are an example of politically incoherent pedagogy. That is to say, they are partially authoritarian and partially not, partially student-empowering and partially not.

Each of these questions is worthy of more serious exploration, with a special emphasis on the last three (the ones I’m not doing). But it’s worth quickly addressing the first four. |

Questions 1-4:

Forgive the obviousness of this statement: students (and especially students at Brooks, who tend to be conscientious and hardworking) are significantly less likely to cheat on assignments when they’re given the necessary time and support to complete them (and complete them well). They’re also less likely to cheat if they understand how to get an “A”—more on grades later—or if the “A” seems attainable. And they’re less likely to cheat if the emphasis is on the process (i.e. all the steps needed to reach the final draft) rather than the product (just turn in the final draft).

In other words: if I say on Monday, “Here’s the prompt and the rubric; complete the final draft for homework and turn it in a week from today,” it shouldn’t surprise me if I receive a significant percentage of ChatGPT essays the following Monday. What I’ve implicitly told them is “I’m not interested in HOW you go about writing this paper; I just care about what you end up with. Get it to me by any means necessary.”

Structurally, students learn to value what you do in class (the fact that you’re doing it in class shows that you care about it and prioritize it), just as they learn to devalue/cheat on what you ask them to do outside of class (the fact that you’re not spending class time on it shows that you value it less than what you’re doing in class). So if I ask my students to complete reading for homework, what I’m implicitly telling them is, “Yeah, I’d like for you to read, but if only about 60% of you do it and the rest of you SparkNote or cheat, that’s not the worst thing in the world; reading isn’t as big a priority in this class as the stuff we’re doing during class.” The same is true of writing. If I ask my students to complete an essay outside of class for homework, the implication is that the writing process isn’t really one of my main concerns. And if the writing process isn’t the point—if the process is just a meaningless Indiana highway rest stop en route to the real destination (let’s say Niagara Falls)—why not use ChatGPT?

Single-draft essays encourage ChatGPT because they devalue the writing process. They also make the threat of grades more threatening—and the temptation to cheat more alluring—because the student is less certain that they’re “doing it right.” If the only time the teacher looks at your work is at the very end, when the summative grade really matters, that’s scary: What if you’ve been doing it totally wrong and you had no idea? Safer to cheat and save yourself the embarrassment (and the grade). If, on the other hand, you’ve conferenced with the teacher on your outline, or the teacher has looked over your rough draft and offered feedback, you can be reasonably confident you’re on the right track. In other words, if the teacher is a partner and tour guide during the writing process—rather than a final boss battle waiting at the end of the writing process—the process becomes less authoritarian, evaluative, and antagonistic, while the student-teacher relationship becomes more cooperative.

Forgive the obviousness of this statement: students (and especially students at Brooks, who tend to be conscientious and hardworking) are significantly less likely to cheat on assignments when they’re given the necessary time and support to complete them (and complete them well). They’re also less likely to cheat if they understand how to get an “A”—more on grades later—or if the “A” seems attainable. And they’re less likely to cheat if the emphasis is on the process (i.e. all the steps needed to reach the final draft) rather than the product (just turn in the final draft).

In other words: if I say on Monday, “Here’s the prompt and the rubric; complete the final draft for homework and turn it in a week from today,” it shouldn’t surprise me if I receive a significant percentage of ChatGPT essays the following Monday. What I’ve implicitly told them is “I’m not interested in HOW you go about writing this paper; I just care about what you end up with. Get it to me by any means necessary.”

Structurally, students learn to value what you do in class (the fact that you’re doing it in class shows that you care about it and prioritize it), just as they learn to devalue/cheat on what you ask them to do outside of class (the fact that you’re not spending class time on it shows that you value it less than what you’re doing in class). So if I ask my students to complete reading for homework, what I’m implicitly telling them is, “Yeah, I’d like for you to read, but if only about 60% of you do it and the rest of you SparkNote or cheat, that’s not the worst thing in the world; reading isn’t as big a priority in this class as the stuff we’re doing during class.” The same is true of writing. If I ask my students to complete an essay outside of class for homework, the implication is that the writing process isn’t really one of my main concerns. And if the writing process isn’t the point—if the process is just a meaningless Indiana highway rest stop en route to the real destination (let’s say Niagara Falls)—why not use ChatGPT?

Single-draft essays encourage ChatGPT because they devalue the writing process. They also make the threat of grades more threatening—and the temptation to cheat more alluring—because the student is less certain that they’re “doing it right.” If the only time the teacher looks at your work is at the very end, when the summative grade really matters, that’s scary: What if you’ve been doing it totally wrong and you had no idea? Safer to cheat and save yourself the embarrassment (and the grade). If, on the other hand, you’ve conferenced with the teacher on your outline, or the teacher has looked over your rough draft and offered feedback, you can be reasonably confident you’re on the right track. In other words, if the teacher is a partner and tour guide during the writing process—rather than a final boss battle waiting at the end of the writing process—the process becomes less authoritarian, evaluative, and antagonistic, while the student-teacher relationship becomes more cooperative.

|

Ironically, this is part of the reason universities are struggling so much with ChatGPT (even more so, arguably, than high schools): college writing assignments are purely product-based. Colleges have never cared about supporting the writing process. Bad collegiate pedagogy, in other words, is finally coming back to bite them.

|

Question 5: Did I let them choose WHAT they’re writing about (the subject/text)?

For me, the answer is usually “no,” which is a problem. Of course, I try to give some choice—i.e. “You can choose between these seven prompts,” “You can choose to write about one of these three texts,” etc—but this isn’t a particularly meaningful form of choice. Their menu of options is still coming from me, and I’m giving them a very small menu, like an exclusive restaurant that only serves three dishes. And when it comes to literary analysis, they basically have one option: This essay has to be about Born a Crime. This essay has to be about The Great Gatsby.

For the vast majority of their schooling, students have very little choice over what subjects they write about (or what books they write about). This is why students don’t grow up to become writers. Real writers are people who have been given permission, somewhere along the line, to develop their own style to write about things that interest them. Most students are never given this permission; very rarely do teachers say to students, “Screw Gatsby—what do you want to write about?” As a result, students learn implicitly that writing is a means to an end—a way to accumulate grade coins—rather than a means of self-exploration, of stylistic exploration. Most school writing is fundamentally transactional: you write this exact thing in this exact way, and in return, I will give you this grade coin. If students choose to expedite this transaction by using ChatGPT, is it really so surprising? If you gave a groundskeeper a more efficient lawn mower, they would use it in a heartbeat. They wouldn’t feel an existential crisis about “depersonalizing” the act of mowing the lawn.

(Incidentally, this is also why most students don’t grow up to be readers. Because they are so rarely given the opportunity to choose their own reading material, students see reading as something that is “about the teacher” rather than something that is “about them.” This is why daily independent reading at the beginning of class is so essential: it puts the power back in the students’ hands. It cultivates a love of reading because it makes reading about the student rather than about the teacher. And because it’s done during class, it shows students that actually reading—rather than fake reading—is one of the class’s top priorities. But I digress.)

As much as it pains me to say it—because I give many traditional writing assignments—traditional writing assignments in schools are rooted in authoritarianism. In other words, they reinforce a dehumanizing power hierarchy; they imply that teachers are somehow more qualified to choose a student’s interests than students are to choose what interests them. Whether or not students rebel against this structure, they ultimately absorb the subconscious message: writing is an inherently impersonal exchange—and thus “outsourceable,” like a multiplication problem, something you may as well have a machine do for you. Part of the tragedy here is that writing, of all things, is one of the most personal acts there is. If you extract the humanity from the writing, you run the risk of extracting the humanity from the student.

|

Going back to ChatGPT: if students have a personal investment in the writing assignment (because they’ve been given significant freedom to choose what they’re writing about), it won’t occur to them to cheat. If I wanted to paint a picture to hang on my wall, I wouldn’t go to Google and type, “Beautiful painting.” If the personal is the point, then cheating becomes counterproductive. But if the personal is beside the point, ChatGPT is unsurprising—just a logical way of speeding up the inevitable transaction.

|

Question 6: Did I let them choose HOW they write this paper? (Or is it extremely formulaic?)

Because writing instruction is so deeply rooted in “safe formulas,” letting students choose HOW they write can feel even more challenging than letting them choose WHAT they write about. I’m certainly guilty of assigning formulaic essays. And should I feel bad about this? The AP Lang test pledges allegiance to these formulas. Most collegiate academic writing pledges allegiance to these formulas. These formulas teach a certain type of rigorous organizational thinking—a hierarchy of arguments and sub-arguments—that’s an undeniably useful intellectual exercise. It’s the easiest thing in the world to justify.

But just because something is easy to justify doesn’t mean it’s good teaching. The obvious irony is that if you look out in the wide world of nonfiction writing—magazine articles, newspaper op-eds, books of exploratory essays, Malcolm Gladwell-esque pop psychology, or even James Baldwin, the dude who’s often celebrated as the greatest essayist of the 20th century—exactly 0% of it adheres to school-taught writing formulas. This is because—and hang onto your hats--these are boring formulas. No magazine editor would ever allow a school-style essay to be published; they know that this depersonalized approach is not a recipe for audience engagement. Rather, these formulas are designed to strip the human element from the essay: to grind students into anonymity and submission by having them write in the exact same way as everyone else. Personal style can exist within these formulas—“Life finds a way” (Jurassic Park)—but if the structure of an essay is PART of its style, assigning a “formula essay” removes half of these stylistic opportunities before the student has written a word.

Of course, I’m not suggesting that we stop asking students to organize their ideas in their writing. And I’m definitely not suggesting that we don’t give students model texts to base their writing on. What I am suggesting is that we provide a broader range of models. In other words, the problem isn’t necessarily that we’re giving students “formulas”; the problem is that we’re essentially giving students the same formula, over and over again (rather than, say, 87 different formulas, showcasing the range of possibilities). This makes the traditional school essay an authoritarian teaching tool. In this case, the authority is the College Board, but this doesn’t make it any less authoritarian.

Because writing instruction is so deeply rooted in “safe formulas,” letting students choose HOW they write can feel even more challenging than letting them choose WHAT they write about. I’m certainly guilty of assigning formulaic essays. And should I feel bad about this? The AP Lang test pledges allegiance to these formulas. Most collegiate academic writing pledges allegiance to these formulas. These formulas teach a certain type of rigorous organizational thinking—a hierarchy of arguments and sub-arguments—that’s an undeniably useful intellectual exercise. It’s the easiest thing in the world to justify.

But just because something is easy to justify doesn’t mean it’s good teaching. The obvious irony is that if you look out in the wide world of nonfiction writing—magazine articles, newspaper op-eds, books of exploratory essays, Malcolm Gladwell-esque pop psychology, or even James Baldwin, the dude who’s often celebrated as the greatest essayist of the 20th century—exactly 0% of it adheres to school-taught writing formulas. This is because—and hang onto your hats--these are boring formulas. No magazine editor would ever allow a school-style essay to be published; they know that this depersonalized approach is not a recipe for audience engagement. Rather, these formulas are designed to strip the human element from the essay: to grind students into anonymity and submission by having them write in the exact same way as everyone else. Personal style can exist within these formulas—“Life finds a way” (Jurassic Park)—but if the structure of an essay is PART of its style, assigning a “formula essay” removes half of these stylistic opportunities before the student has written a word.

Of course, I’m not suggesting that we stop asking students to organize their ideas in their writing. And I’m definitely not suggesting that we don’t give students model texts to base their writing on. What I am suggesting is that we provide a broader range of models. In other words, the problem isn’t necessarily that we’re giving students “formulas”; the problem is that we’re essentially giving students the same formula, over and over again (rather than, say, 87 different formulas, showcasing the range of possibilities). This makes the traditional school essay an authoritarian teaching tool. In this case, the authority is the College Board, but this doesn’t make it any less authoritarian.

|

If teachers begin by telling students both WHAT they’re going to write about and HOW they’re going to write about it, they’ve already given the student the vase and the flowers; the student’s only job is to fill the vase with water. But that’s the least exciting—and the least personal—part of the process. If, as a student, my intuition tells me that the assignment, at its very root, has nothing to do with me—that all meaningful choice has been removed from the process—why shouldn’t I use ChatGPT? It’s a depersonalized solution to a depersonalized task.

|

Question 7: Did I successfully remove the external motivator of “grades” from this writing process so that students are invested in the process for its own sake? (Or is there a big scary grade waiting for them at the end that will partially determine their GPA/financial security/future opportunities?)

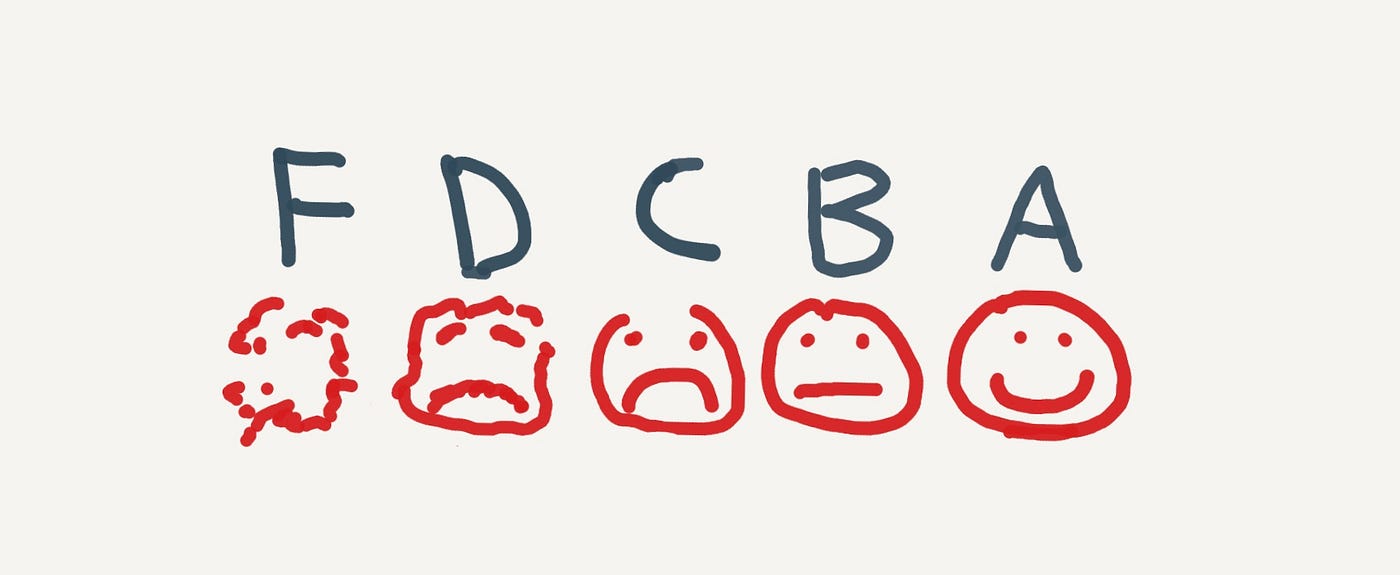

Recently, Mr. Wilde and I have been debating about rubrics. (Thrilling, I know.) My current rubric is on a four-point scale, the traditional “standards-based grading” model. Wilde argues in favor of the “one point rubric”: in other words, the student is either “meeting expectations” or “not meeting expectations,” with nothing in between. Wilde’s (extremely rational) argument is that we shouldn’t accept work that doesn’t meet all standards; all that does is teach students that subpar work is OK. If students don’t meet all standards, Wilde gives feedback and has them redo it until they do meet all standards. This is a logical and humane approach.

The irony is that Mr. Wilde and I are probably both wrong (though Wilde is more right than I am; he is Mr. Wilde, after all). Both of our grading policies are predicated on giving grades, so they were doomed from the start.

Recently, Mr. Wilde and I have been debating about rubrics. (Thrilling, I know.) My current rubric is on a four-point scale, the traditional “standards-based grading” model. Wilde argues in favor of the “one point rubric”: in other words, the student is either “meeting expectations” or “not meeting expectations,” with nothing in between. Wilde’s (extremely rational) argument is that we shouldn’t accept work that doesn’t meet all standards; all that does is teach students that subpar work is OK. If students don’t meet all standards, Wilde gives feedback and has them redo it until they do meet all standards. This is a logical and humane approach.

The irony is that Mr. Wilde and I are probably both wrong (though Wilde is more right than I am; he is Mr. Wilde, after all). Both of our grading policies are predicated on giving grades, so they were doomed from the start.

|

The problem is grades. Students don’t cheat to get good grades; grades are the structural reason that students cheat in the first place. This may sound like semantics. It’s not. If grades didn’t exist, students wouldn’t cheat.

Cool, you may be thinking. So that’s your bright idea for combatting ChatGPT? Eliminate grades? OK, I’ll start doing that in my classroom tomorrow. |

But grades are the true final boss battle when it comes to anti-authoritarian teaching. Grades make everything in education transactional. Grades reduce everything students do in school to the lowest common denominator: the number. Grades make it so that nothing in school matters for its own sake—or if it does matter, it’s in spite of a system that discourages personal engagement. As Alfie Kohn has frequently pointed out, grades make it so that all student work is externally motivated: students’ primary reason for completing work is always to avoid an external threat (“the bad grade”—or its cousins, “the disappointed parent” and “the skeptical college admissions officer”). If that sounds normal, it’s only because our society has successfully normalized a dystopian system where no one does anything for the intrinsic value of the task itself. In this dystopian system, education has nothing to do with the person getting educated; the very best students are those who have somehow managed to a) believe in these external motivators with an almost religious devotion, b) accept that school is fundamentally impersonal (and be OK with that), and/or c) find pockets of personal interest in spite of a system that has externalized all motivation. This is a lot to ask of a child.

Grades also make every teacher an antagonist whether we like it or not. If we acknowledge, as I think everyone does, that grades eventually lead to significant real-world consequences—scholarships, college admissions, job opportunities, financial security (or precarity), crushing debt (or lack thereof), home ownership, etc—then structurally, every teacher becomes an “obstacle” standing between the student and a comfortable life. Different teachers wield this staggering power differently, but regardless whether this uncomfortable power dynamic is highlighted or minimized, it always exists.

Grades also make every teacher an antagonist whether we like it or not. If we acknowledge, as I think everyone does, that grades eventually lead to significant real-world consequences—scholarships, college admissions, job opportunities, financial security (or precarity), crushing debt (or lack thereof), home ownership, etc—then structurally, every teacher becomes an “obstacle” standing between the student and a comfortable life. Different teachers wield this staggering power differently, but regardless whether this uncomfortable power dynamic is highlighted or minimized, it always exists.

Students read a lot of dystopian books and watch a lot of dystopian movies—which effectively disguises the fact that the world we live in is already dystopian (albeit in more subtle ways than, say, “children forced to fight each other to the death in televised game shows”). Grades are a dystopian, authoritarian institution. They teach students to be subservient, to accept powerlessness and prioritize others’ evaluations and judgments over their own. They teach students that no task is worth doing for its own sake. They teach students that all of their actions are reducible to numbers. They prepare students for a capitalist future in which all of their actions will also be reducible to numbers.

The hand-wringing over ChatGPT, then, isn’t necessarily wrong, but it is misguided, disguising a more disturbing truth: both ChatGPT and grades are dystopian technologies deeply aligned with an authoritarian education system. They both emphasize product over process. They are both excellent technologies for producing empty, depersonalized work. They are both efficient ways to remove the child from the learning process. They are both the offspring of a transactional education system that reduces everything to mindless inputs and outputs. And of course, without the omnipresent threat of grades, students would have no reason to use ChatGPT. If one of these technologies feels dystopian and the other doesn’t, it is only because we’ve had more time to get used to it.

The hand-wringing over ChatGPT, then, isn’t necessarily wrong, but it is misguided, disguising a more disturbing truth: both ChatGPT and grades are dystopian technologies deeply aligned with an authoritarian education system. They both emphasize product over process. They are both excellent technologies for producing empty, depersonalized work. They are both efficient ways to remove the child from the learning process. They are both the offspring of a transactional education system that reduces everything to mindless inputs and outputs. And of course, without the omnipresent threat of grades, students would have no reason to use ChatGPT. If one of these technologies feels dystopian and the other doesn’t, it is only because we’ve had more time to get used to it.

There are a lot of educators doing fascinating, progressive work on how to go about “ungrading” in the classroom (Sarah Zerwin, for one; my wife, for another). That isn’t the point of this article—whole books have been written about this knotty subject—but it’s worth noting that this isn’t a fanciful idea, and that thousands of educators around the country are taking this seriously as an alternative.

The good news about ChatGPT is that it forces the issue. It makes visible what was previously invisible, and it demands a more progressive, student-empowering pedagogy than more traditional practices we’ve been able to rely on for generations. To recap:

1) Students won’t use ChatGPT if the threat of grades is removed from the equation.

2) Students won’t use ChatGPT if they’re empowered to choose what they write about and how they write about it; if the personal is the point, cheating becomes counterproductive.

3) Students won’t use ChatGPT if the emphasis is on the writing process (annotations, outline, rough draft, revisions, final draft) rather than the product.

4) Students won’t use ChatGPT if they have enough support (via clear expectations and scaffolding, model texts, individualized feedback, conferences) and time (both in and out of class) to complete the assignment (and to be sure of completing the assignment well).

This isn’t radical pedagogy. It’s the same anti-authoritarian pedagogy we should’ve been doing all along.

The good news about ChatGPT is that it forces the issue. It makes visible what was previously invisible, and it demands a more progressive, student-empowering pedagogy than more traditional practices we’ve been able to rely on for generations. To recap:

1) Students won’t use ChatGPT if the threat of grades is removed from the equation.

2) Students won’t use ChatGPT if they’re empowered to choose what they write about and how they write about it; if the personal is the point, cheating becomes counterproductive.

3) Students won’t use ChatGPT if the emphasis is on the writing process (annotations, outline, rough draft, revisions, final draft) rather than the product.

4) Students won’t use ChatGPT if they have enough support (via clear expectations and scaffolding, model texts, individualized feedback, conferences) and time (both in and out of class) to complete the assignment (and to be sure of completing the assignment well).

This isn’t radical pedagogy. It’s the same anti-authoritarian pedagogy we should’ve been doing all along.

It’s easy to blame teachers for recreating authoritarian practices in the classroom, but blaming teachers misses the point: teachers, just like students, are beholden to larger structures that strongly encourage certain teaching practices (and strongly discourage others). It’s possible for a trout to swim against the current, but it’s extremely difficult; eventually, the trout will probably be swept away with the current like everyone else.

But in this regard, ChatGPT might prove to be a powerful tool—not only for auto-generating robotic, unreadable Born a Crime essays, but also for revealing the impersonal absurdity of many of our current teaching practices. ChatGPT shoves our faces into the mess we’ve made and says, “This is what your practices hath wrought; do you like it?”

In other words, the rise of ChatGPT doesn’t represent the shocking emergence of a brand new problem; it highlights the same authoritarian problems we’ve had for generations. It just makes them harder to ignore.

But in this regard, ChatGPT might prove to be a powerful tool—not only for auto-generating robotic, unreadable Born a Crime essays, but also for revealing the impersonal absurdity of many of our current teaching practices. ChatGPT shoves our faces into the mess we’ve made and says, “This is what your practices hath wrought; do you like it?”

In other words, the rise of ChatGPT doesn’t represent the shocking emergence of a brand new problem; it highlights the same authoritarian problems we’ve had for generations. It just makes them harder to ignore.