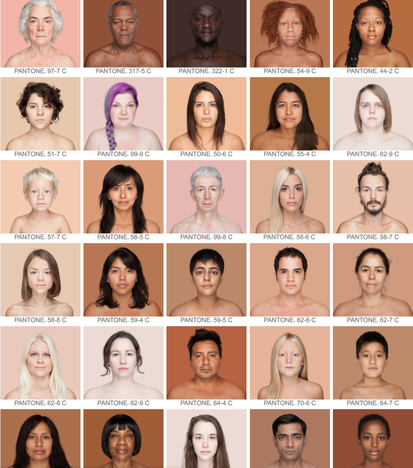

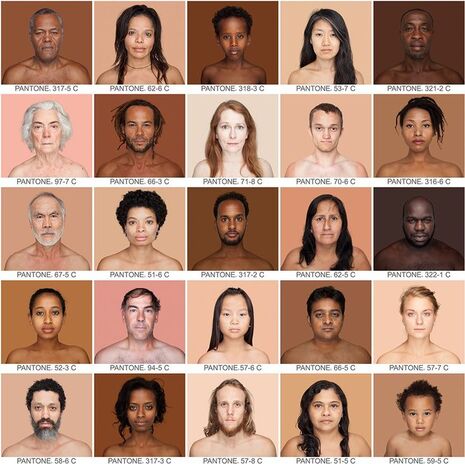

How many colors are there in the human rainbow? By Angelica Dass’s count, at least 4,000. Since 2012, the Brazilian award-winning artist has been photographing people of every color and matching each person’s skin tone to hues from the Pantone printing color chart. Angelica shows through her portraits that skin color is nothing more than a shade in the Pantone scale and a historical construct. She advocates for social change, promotes communication, and challenges cultural prejudices. Today, her TedTalk has over 2.5 million views and has been translated to 34 languages. The artist’s multi-ethnic family were her first subjects. Since then, she’s taken 4,000 portraits in 18 different countries, and there’s no end in sight.

Dass’s exploration of our skin tones is based on an 11-by-11-pixel sample taken from each person’s nose. She then matches it to a color card from Pantone, which she uses as the backdrop for the person’s portrait. Below each picture, Dass prints the official Pantone number--her own is “7522 C,” a warm brown. “Using this scale, I am sure that nobody is “black,” and absolutely nobody is “white”.These kinds of concepts that we used in the past are completely nonsense,” Dass told Newsweek, pointing out how many people from vastly different ethnicities sometimes wind up with the exact same Pantone color. But whereas Pantone’s library only has 1,867 colors, there is no end to the shades in the human spectrum. Her concept artwork is having a big impact on educating young people. The Humanae Project led to the creation of the non-profit organization that helps teachers and educators make children think critically about race, identity, and the labels that seperate us. She collaborates with several educators and schools around the world, especially in Madrid (Spain) where she currently lives.

Since 2012, Humanae has been collecting portraits of people around the world in a pursuit to document humanity’s true colors rather than the untrue white, red, black, and yellow that have been associated with race for centuries. According to Dass, “I’ll keep working with Humanae because it is necessary. Until I won’t stop being dehumanized because of the way I am, black, immigrant, Latina.” It’s essential to keep fighting to show that ethnicity, cultural differences, neurodiversity, and LGBTQ rights, are labels that define only a small part of you, because “biologically, we are 99.9% made from the exact same material.” Humanae will never be finished. Dass can never photograph everyone in the world, let alone capture each of their skin tones as they appear in summer and winter. That is part of the point. “People ask,'' Oh, how many colors do you have?,” she says “I have no idea, and I really don’t care.” Society as a whole has to do the work, one person at a time, that includes individual reflections and personal stories of supporting, silencing, and being indifferent when seeing a racist act or comment.

Since 2012, Humanae has been collecting portraits of people around the world in a pursuit to document humanity’s true colors rather than the untrue white, red, black, and yellow that have been associated with race for centuries. According to Dass, “I’ll keep working with Humanae because it is necessary. Until I won’t stop being dehumanized because of the way I am, black, immigrant, Latina.” It’s essential to keep fighting to show that ethnicity, cultural differences, neurodiversity, and LGBTQ rights, are labels that define only a small part of you, because “biologically, we are 99.9% made from the exact same material.” Humanae will never be finished. Dass can never photograph everyone in the world, let alone capture each of their skin tones as they appear in summer and winter. That is part of the point. “People ask,'' Oh, how many colors do you have?,” she says “I have no idea, and I really don’t care.” Society as a whole has to do the work, one person at a time, that includes individual reflections and personal stories of supporting, silencing, and being indifferent when seeing a racist act or comment.

Reflecting on the events that raised awareness about police brutality towards African Americans, Angelica confessed that when living in the U.S. a few years ago, she was afraid to walk down the streets alone. This fear should be understood. For Angelica, it wasn’t only nine minutes of asphyxia from the knee of the cop in George Floyd’s neck, but all his life, and for Angelica, “It’s been 41 years.” It’s suffocating. The American Museum of Natural History of New York has included a special exhibit featuring an installation of Angelica’s portraits showcasing the diversity of humans from around the world. In addition, since 2017, the small town of Kingsport, Tennessee has had a mural in the middle of the town with Humanae Project portraits reminding citizens that we are all the same, with integrity, dignity, and at the same time different. After all, respecting each other is respecting our humanity.